“How do you make a femtosecond light source?”

Why did you get involved in X-ray science?

Part of it was Claudio—he’s a very charismatic character. He’s an inspiring character. The field was very interesting. I thought it was a good way to spend my PhD.

LCLS was promising so much innovation: a laser 10 billion times brighter than we had then. That sounds like something that somebody who is 24 would love to get involved in. It just sounded like something that would change science in a positive way, and I wanted to be a part of it.

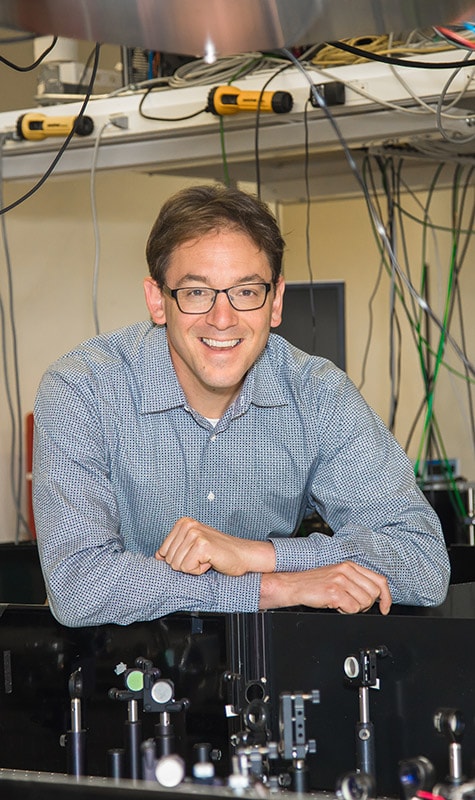

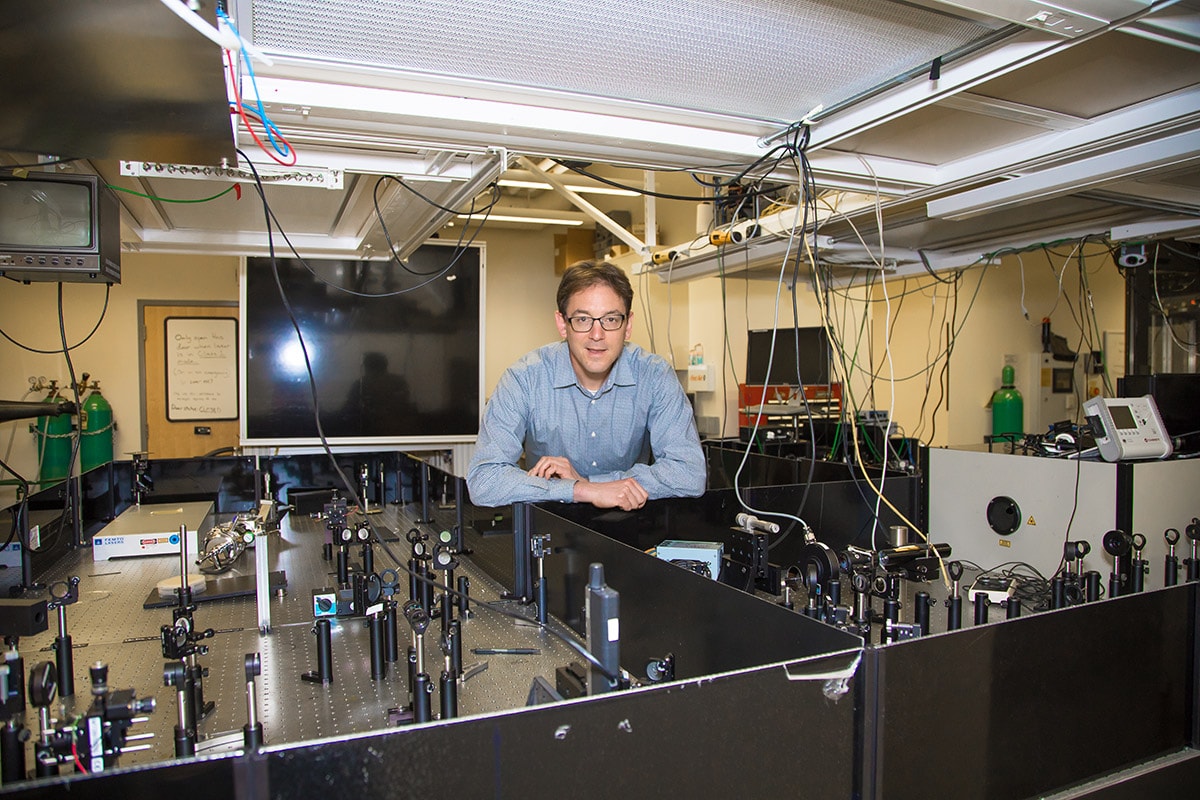

Agostino Marinelli

What is a free-electron laser?

Free-electron lasers were invented by John Madey at Stanford in 1971; later on in the ’90s Claudio Pellegrini and collaborators proposed to extend free-electron lasers to the X-ray regime. They were the next step after synchrotron light sources.

Synchrotrons send electrons around in a circle. That gives you radiation you can use in experiments. The difference between a synchrotron and the free-electron laser is the same difference between this light [points to a ceiling light] and a laser. It’s the difference between a bunch of kids making noise and a choir.

In a synchrotron, the electrons are all doing the same thing, going around in a circle, but they are unaware of each other. They are all emitting X-rays in a random way. What makes a free-electron laser a laser is that all the electrons are emitting radiation in a coherent way. They are all synchronized.

Also, since in an FEL you are using very intense and short electron bunches, the X-ray pulses will also be very short, down to the femtosecond level.

Watch Marinelli's talk "Introduction to the Physics of Free Electron Lasers"

Agostino Marinelli

What do you do with the free-electron laser?

We talk to the users—they’re researchers that have some science they want to study with the machine. Then we “shape” the X-rays—set up the machine in a way that’s ideal for that experiment. The LCLS accelerator is very flexible. You can do all sorts of tricks with it—like arbitrarily changing the pulse duration, varying the X-ray polarization or making multiple pulses of different colors.

Agostino Marinelli

Speaking of which, in 2014 the European Physical Society awarded you the Frank Sacherer Prize for your work using “two-color” beams with LCLS. What is that about?

Normally LCLS shoots 120 X-ray pulses a second. But you can also make it send two pulses of different energies, separated by a few to 100 femtoseconds. You excite your sample with the first one and probe it with the second. You have to observe it within femtoseconds after you excite it because reactions happen that fast.

Normally you would excite the sample with an external optical laser; that’s how pump-probe is done. But in molecular dynamics, if you can excite a molecule with X-rays instead of an optical laser, you can get atom specificity—you can target a specific atom in the molecule.

Each atom has a core energy level. If you know that, you can shoot the X-ray and hit only the oxygen in a molecule; oxygen is the only thing that is going to react. With two pulses at separate energies, you can target different atoms in a molecule to see which one triggers a certain reaction.

Fun fact: These pulses are called a “twin bunch,” and in 2016 Marinelli became the father of twins.

Agostino Marinelli

What kinds of things do you study on the femtosecond scale?

A femtosecond is close to the fundamental scale of atomic and molecular physics—so, things like chemistry.

A chemical reaction is essentially two molecules or atoms interacting in some way and sharing charge and giving away energy. Ultimately to understand that, you have to understand how charge and energy flow in a molecule. You have to understand the very fundamental motion of electrons and ions in the molecule. On the femtosecond scale, you can see the positions of the atoms rearranging as it happens.

Chemical reactions are a dynamic process. They start with something. They end with something. We want to know what happens in between.

Agostino Marinelli

Why?

If you want the reaction to end with something else, if you want it to end with something slightly different, you want to understand how it happens so you can make changes on purpose.

Agostino Marinelli

What are you most excited about now?

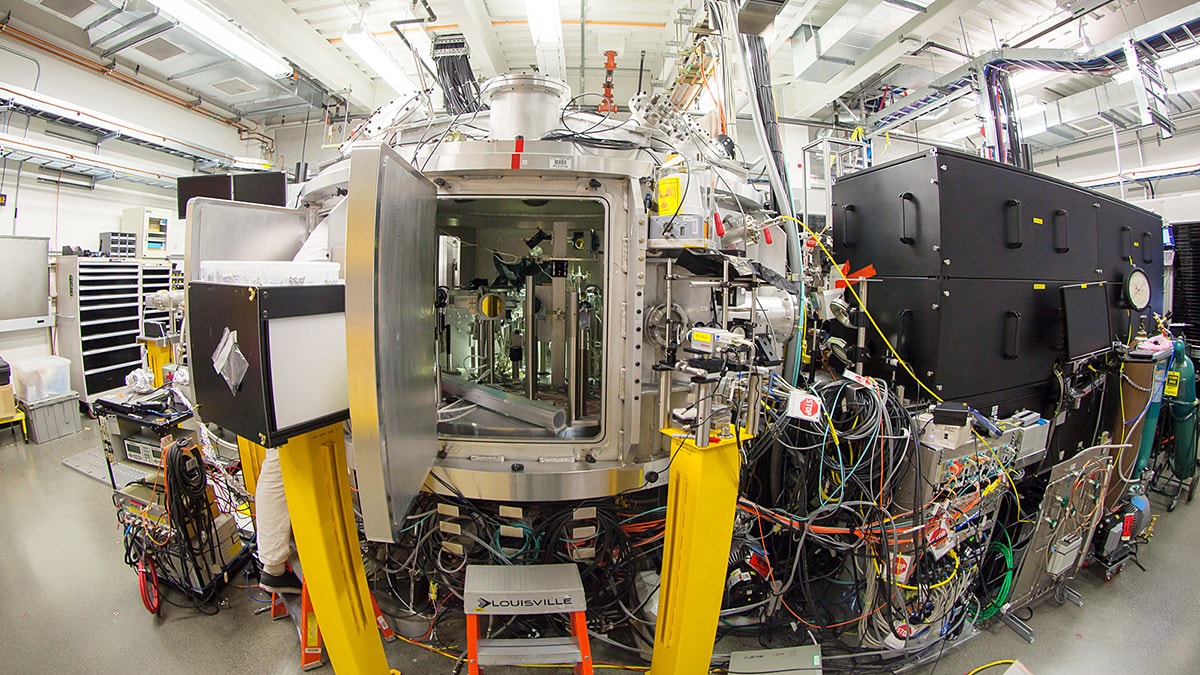

I’m really excited about what I’m about to do, which is this sub-femtosecond project called XLEAP. We will shape the LCLS electron beam with a high-power infrared laser and use it to generate pulses that are shorter than a femtosecond! What we will be looking at is energy and electrons moving around a molecule, which happens even faster than the atoms rearranging.

Right now we’re really blind to all of this. To me, the way I understand it is, going to that timescale, you’re peeking into the very fundamental, quantum nature of the electrons in the molecule.

If you ask me, “What is the ultimate problem it will solve for us?”—the answer is: I don’t know. In general when you’re blind to some fundamental process in nature and suddenly you can see it, my guess is something good is going to come of it.

Agostino Marinelli

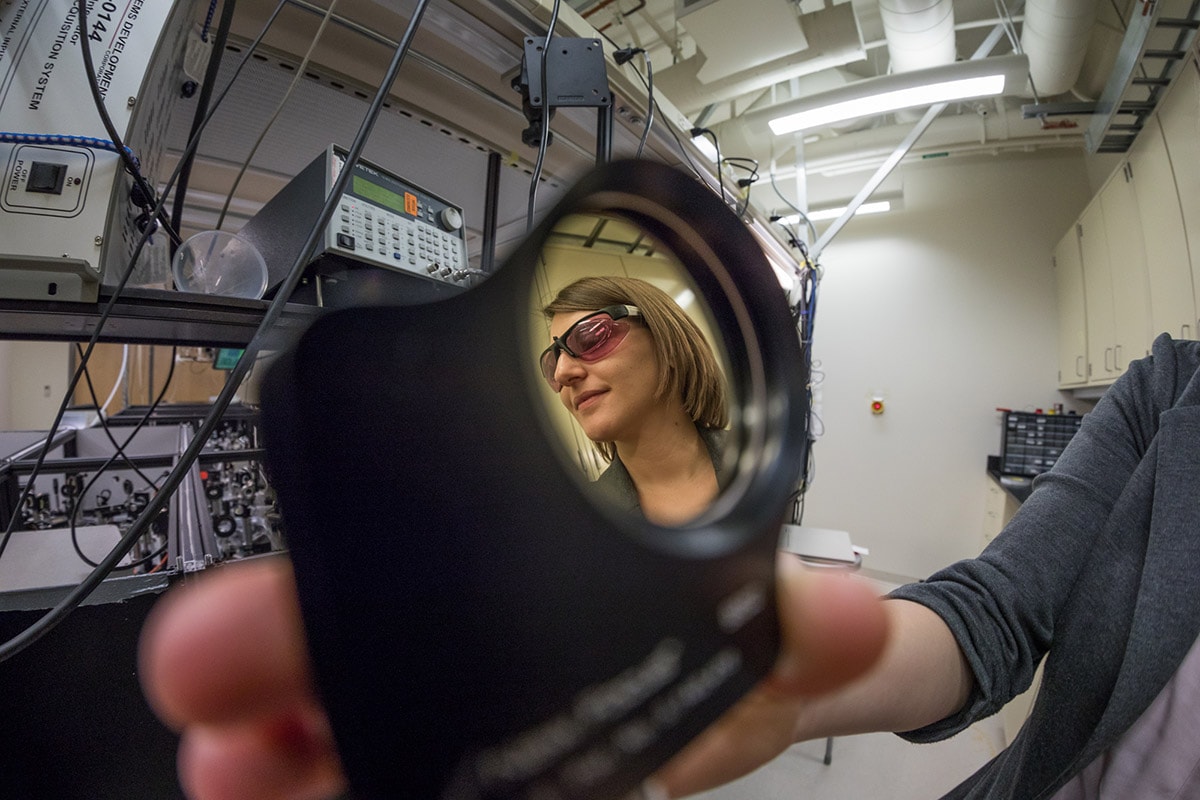

“How do you catch femtosecond light?”

When did you begin working with detectors?

I moved to the United States as a doctoral student. My professor at the time suggested I join a collaboration at Brookhaven National Laboratory, where I started developing gamma ray detectors to catch radioactive materials.

Radioactive materials give off gamma rays as they decay, and gamma rays are the most energetic photons, or particles of light. The detectors I worked on were made from cadmium zinc telluride, which has very good stopping power for highly energetic photons. These detectors can identify radioactive isotopes for security—such as the movement of nuclear materials—and contamination control, but also gamma rays for medical and astrophysical observations.

Radioactive materials give off gamma rays as they decay, and gamma rays are the most energetic photons, or particles of light. The detectors I worked on were made from cadmium zinc telluride, which has very good stopping power for highly energetic photons. These detectors can identify radioactive isotopes for security—such as the movement of nuclear materials—and contamination control, but also gamma rays for medical and astrophysical observations.

We had some medical projects going on at the time, too, with detectors that scan for radioactive tracers used to map tissues and organs with positron emission tomography.

From gamma ray detectors, I then moved to X-rays, and I began working on the earliest detectors for LCLS.

Gabriella Carini

How do you explain your job to someone outside the X-ray science community?

I say, “There are three ingredients for an experiment—the source, the sample and the detector.”

You need a source of light that illuminates your sample, which is the problem you want to solve or investigate. To understand what is happening, you have to be able to see the signal produced by the light as it interacts with the sample. That's where the detector comes in. For us, the detector is like the “eyes” of the experimental set-up.

Gabriella Carini

What do you like most about your work?

There’s always a way we can help researchers optimize their experiments, tweak some settings, do more analysis and correction.

There’s always a way we can help researchers optimize their experiments, tweak some settings, do more analysis and correction.

This is important because scientists are going to encounter a lot of different types of detectors if they work at various X-ray facilities.

I like to have input from people who are running the experiments. Because I did experiments myself as a graduate student, I’m very sensitive to whether a system is user-friendly. If you don’t make something that researchers can take the best advantage of, then you didn’t do your job fully.

And detectors are never perfect, no matter which one you buy or build.

There are a lot of people who have to come together to make a detector system. It’s not one person’s work. It’s many, many people with lots of different expertise. You need to have lots of good interpersonal skills.

Gabriella Carini

What are some of the challenges of creating detectors for femtosecond science?

In more traditional X-ray sources the photons arrive distributed over time, one after the other, but when you work with ultrafast laser pulses like the ones from LCLS, all your information about a sample arrives in a few femtoseconds. Your detector has to digest this entire signal at once, process the information and send it out before another pulse comes. This requires deep understanding of the detector physics and needs careful engineering. You need to optimize the whole signal chain from the sensor to the readout electronics to the data transmission.

We also have mechanical challenges because we have to operate in very unusual conditions: intense optical lasers, injectors with gas and liquids, etc. In many cases we need to use special filters to protect the detectors from these sources of contamination.

And often, you work in vacuum. With “soft” or low-energy X-rays, they are absorbed very quickly in air. Your entire system has to be vacuum-compatible. With many of our substantial electronics, this requires some care.

So there are lots of things to take into account. Those are just a few examples. It’s very complicated and can vary quite a bit from experiment to experiment.

Gabriella Carini

Is there a new project you are really excited about?

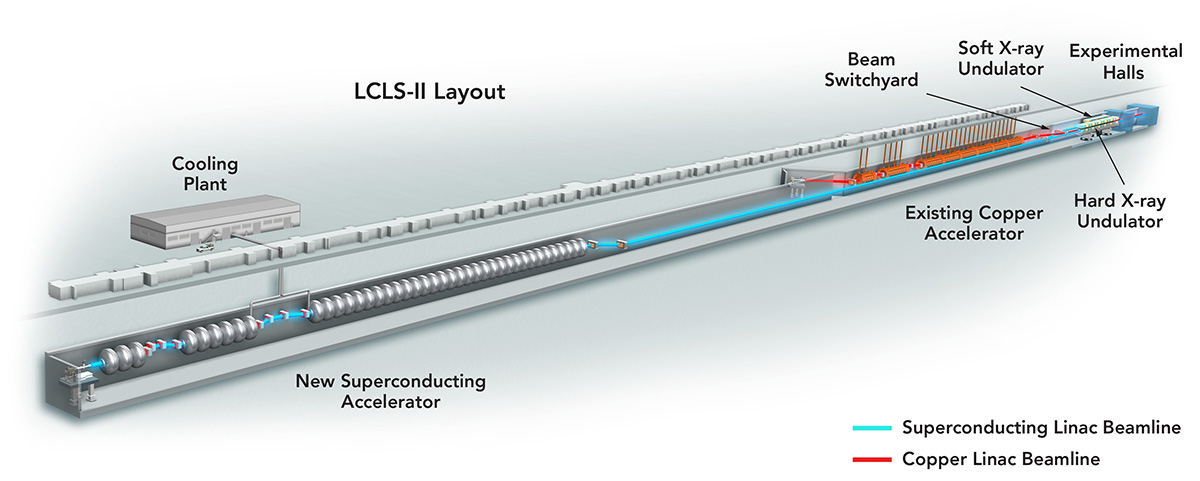

All of LCLS-II—this fills my life! We’re coming up with new ideas and new technologies for SLAC’s next X-ray laser, which will have a higher firing rate—up to a million pulses per second. For me, this is a multidimensional puzzle. Every science case and every instrument has its own needs and we have to find a route through the many options and often-competing parameters to achieve our goals.

X-ray free-electron lasers are a big driver for detector development. Ten years ago, no one would have talked about X-ray cameras delivering 10,000 pictures per second. The new X-ray lasers are really a game-changer in developing detectors for photon science, because they require detectors that are just not readily available.

LCLS-II will be challenging, but it’s exciting. For me, it’s thinking about what we can do now for the very first day of operation. And while doing that, we need to keep pushing the limits of what we have to do next to take full advantage of our new machine.

Gabriella Carini

“What can you study in femtoseconds?”

~ Biology & Chemistry ~

Tell us more about what led you to chemistry research.

Growing up in Durham, North Carolina I had a really great high school chemistry teacher. We had an open period, sort of like study hall, and my teacher allowed me to use that time to do experiments with him in his lab. I did some reading beyond what we had learned in basic chemistry class and learned more about how to put together an experiment.

Growing up in Durham, North Carolina I had a really great high school chemistry teacher. We had an open period, sort of like study hall, and my teacher allowed me to use that time to do experiments with him in his lab. I did some reading beyond what we had learned in basic chemistry class and learned more about how to put together an experiment.

Then I went to Brandeis University, which has a great program getting undergraduate students to do research, and I worked in a biochemistry lab. In graduate school at UC-Berkeley I got interested in how electrons move around in nanocrystals and in studying the processes that impede the efficient use of nanocrystals in solar cells and LEDs. That’s where I started working with ultrafast lasers.

After a postdoc at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where I learned how to use X-ray techniques to study how electrons move around in molecules, I came to SLAC in September 2015.

Amy Cordones-Hahn

What do you look at on femtosecond timescales?

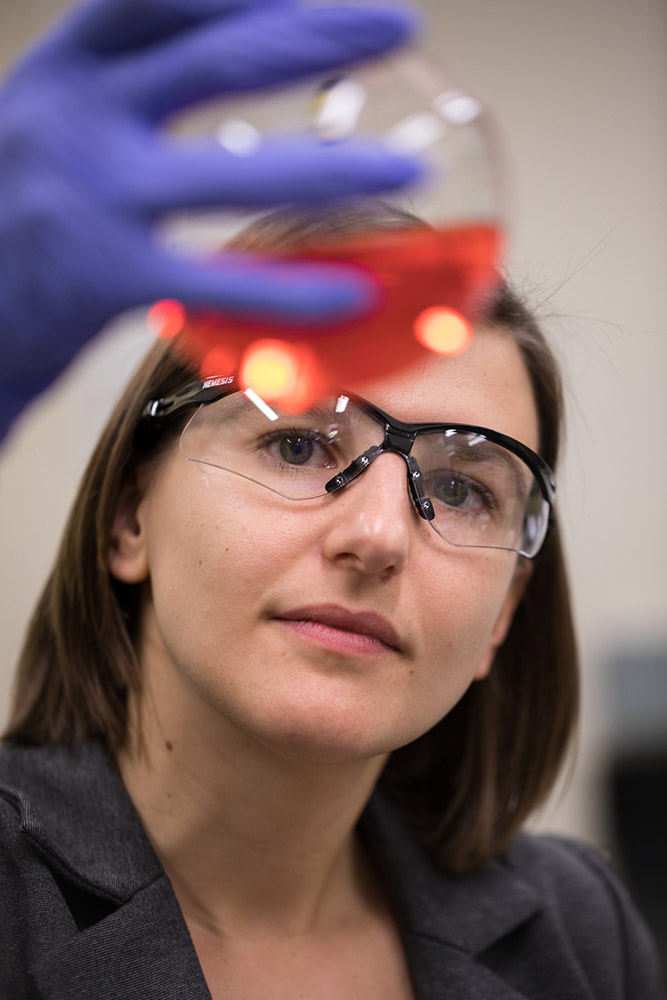

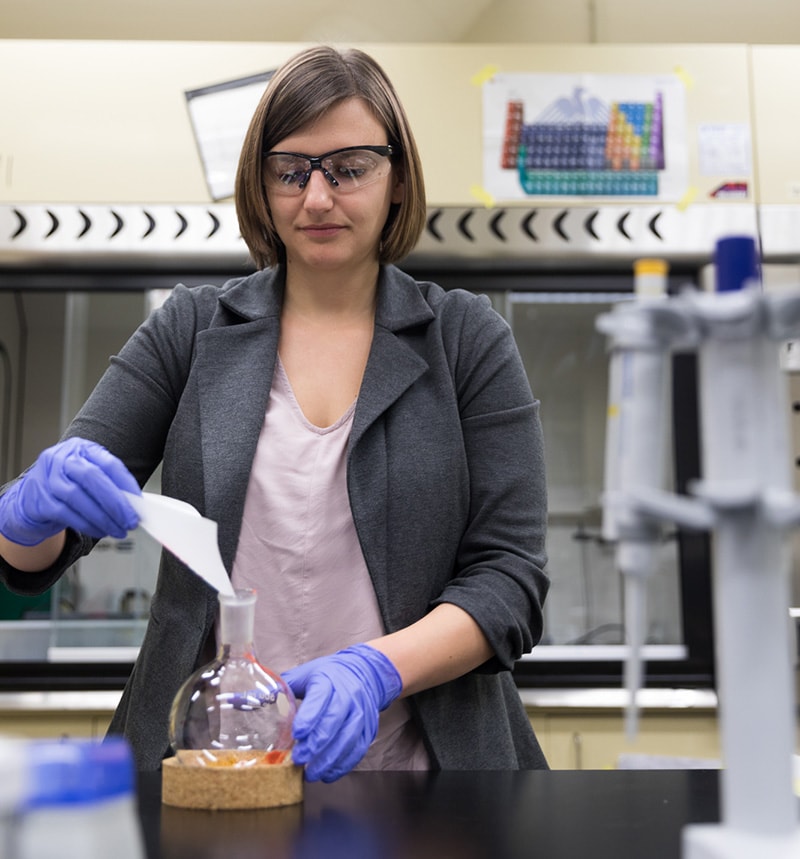

One class of reactions we’ve been studying converts sunlight to electricity or fuel. In biology this is photosynthesis, which plants use to convert sunlight into fuel or sugar. In chemistry, people are trying to mimic those natural processes to create materials or molecules that can absorb sunlight and convert that into a fuel source – hydrogen, for example – or into electricity.

In our group we are really looking at fundamental processes, not trying to create a device. We look at the very fast, initial steps where a single photon, or particle of light, is absorbed by a single molecule.

In general, chemical changes are driven by moving electrons. We use light to give energy to a molecule’s outermost electrons so they can move around and reconfigure themselves. As the electrons move, the force fields felt by the atoms change and the atoms move in response to this change. This causes the bonds between atoms to break and form or just to change, bend and stretch.

With X-rays you can measure where the electrons are sitting with atomic resolution and see how their distribution changes. You are seeing chemistry happen in real time, and you are seeing exactly what the mechanism of a chemical reaction is.

Amy Cordones-Hahn

Almost like watching a movie.

Exactly. In fact, we use SLAC’s X-ray laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), to make “molecular movies” that show how molecules respond to light.

First we hit the molecule with a pulse from an optical laser. The energy from the light pulse makes the electrons and the bonds between the atoms shift around. Then we immediately hit the molecule with an X-ray laser pulse from LCLS. The way the X-rays interact with the molecule gives us a snapshot of how its electron configuration and atomic structure changed in response to the light.

By making a series of these X-ray snapshots, about 50 femtoseconds apart, we get a nice picture—like frames of a movie—of how the light-struck molecule evolves over time. It’s like having a camera with an incredibly bright flash that shoots 20,000,000,000,000 frames per second.

Amy Cordones-Hahn

Do these experiments have any practical benefit?

They do have potential benefits down the road.

For example, our group has been doing a lot of work on dyes that are added to solar cells. They allow the cell to absorb a bigger fraction of the sun’s energy and generate more electricity. The most common dyes are based on the metal ruthenium, which is really efficient but also rare and expensive. We would like to use iron instead, which is cheaper and more abundant, but dyes made with iron don’t work as well; they quickly become deactivated. We are trying to find out why, and these X-ray snapshots are helping us unravel the deactivation process.

We’re also doing work on photocatalysts—molecules that absorb light and use that energy to convert hydrogen ions that are floating in a solution into hydrogen gas for fuel. Other groups have shown that nickel-based photocatalysts can carry out this reaction; now we are trying to find out exactly how it proceeds.

Our hope is that the knowledge we gain from these femtosecond studies will help researchers find ways to make these processes work better.

Amy Cordones-Hahn

“What can you study in femtoseconds?”

~ High Energy Density Science ~

What exactly is “high energy density science”?

It means you have matter or material with a lot of energy in it. The energy is so densely packed that the material is under enormous pressure. So “high energy density science” can also stand for “material at extreme pressure.”

Siegfried Glenzer

How do you create these extreme environments?

We need a powerful laser to start with. We focus those laser beams to tiny spots—like on the micron scale. A human hair is 50 microns, and these spots are a tenth of the diameter of a human hair.

Putting a lot of energy in a very small area produces “high energy density” science. We want to measure the physical properties of these materials.

Siegfried Glenzer

What can we learn from these measurements?

It’s important for our knowledge of how the planets came about, the evolution of the cosmos. And it’s also important for our endeavor to create fusion energy.

Energy in the sun is produced by nuclear fusion. If we can reproduce that on the planet in a controlled way, we have the perfect energy source.

There are also practical, near-term applications. For example, in order to create the extreme material states, we are using powerful lasers. And we discovered that when we fire those laser beams at materials, we accelerate particles to high energies. Where those lasers interact with the materials very energetic particles are produced—protons, electrons, hadrons, X-rays and gamma rays.

These particle movements lead to an instability that can create a shockwave. We can form the instabilities that lead to collisions, so we have a control mechanism, and we just discovered that. What we believe we can do is use that process to our advantage to accelerate particles. So we could have a proton source where we could produce a proton beam at very high energies. That’s currently being investigated as a way to treat cancer.

This is one of the advantages of lasers—they’re so versatile. We do laboratory astrophysics, we do fusion energy discovery science, and we do very practical accelerator physics for tumor therapy.

Siegfried Glenzer

Why is the timescale important? Why do you need an ultrafast laser?

In this realm of science, a series of processes are happening, all on the femtosecond timescale.

The laser interacts with electrons in the materials in femtoseconds, and the light pushes around the electrons. The electrons gain energy and stream through a target. Magnetic fields form around the energized electrons that can coalesce and form a shockwave. That’s called a “collisionless shock.”

That process has been conjectured to be the origin of cosmic rays. Cosmic rays are one of the fundamental processes that mankind still seeks to understand. They are the most energetic particles that we know of. It’s a million times more energetic than what we can produce on Earth at the Large Hadron Collider. And we are looking for the process that explains how these energetic particles came about.

In addition to the high power optical lasers that create these extreme conditions, we also have an intense X-ray beam, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). This laser also has femtosecond capabilities—we can create ultrafast pulses—but at a higher energy than visible light. The X-ray laser allows us to take snapshots of the incredibly fast processes that occur.

So we’ve done experiments where we fire an optical laser on a small piece of carbon, create this environment where the electrons are being pushed out and create shockwaves, and then use X-rays to visualize the shockwaves.

Siegfried Glenzer

These processes might happen in femtoseconds, but how long will it take to create a fusion energy source?

One of the big misconceptions is that people think it cannot happen. They don’t like thinking on a 20- or 30-year timescale. But there are now fusion experiments happening all over the world. We’re making progress. People just have to accept that science can take more than a year or two to see results. It may take decades.

Fusion is happening every day in the sun, so all we have to do is look up in the sky and ask “Can we control it in the laboratory? How bright are we? And how willing are we as a community to make it happen?”

Siegfried Glenzer

“What can you study in femtoseconds?”

~ Materials ~

What excites you most about your research?

When microscopes were invented, they let us see bacteria for the first time. Telescopes allowed us to glimpse moons orbiting faraway planets. Now the modern tools of femtosecond science provide a completely new way of seeing what’s really going on in materials and devices around us.

These tools are basically advanced cameras that take very sharp images of individual atoms. We then string these images together into movies of ultrafast atomic motions. This information not only helps us understand how materials get their unique properties; it also gives us clues for making them better, because in many cases these very fast processes determine how materials function.

In solar cells, for instance, rapid motions of atoms and electrons affect how efficiently sunlight is converted into electricity. In two-dimensional materials, which are only a few atoms thick, ultrafast motions are closely linked to unique properties that make these materials interesting for high-performance chemical catalysts, fast and flexible electronics, photonic devices such as solar cells, and other applications.

Aaron Lindenberg

How do these advanced cameras work?

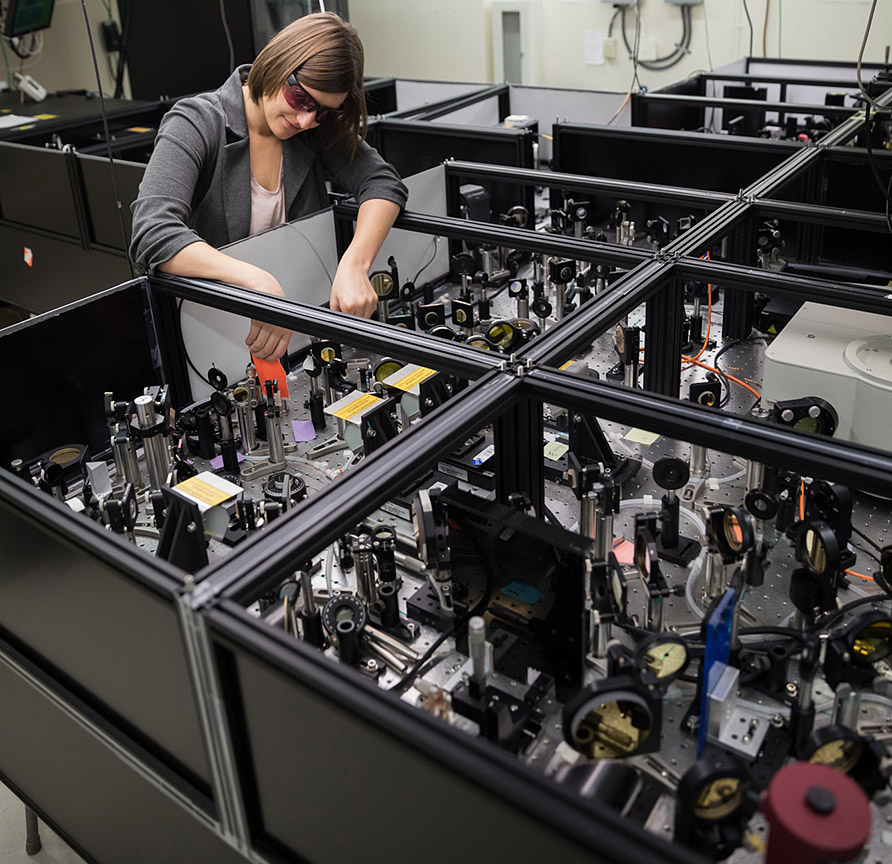

The principle behind them is very similar to high-speed flash photography, in which you take a series of snapshots of an object with a fast strobe light. This allows you to capture things you normally don’t see, such as a hummingbird flapping its wings. The faster the flashes, the faster the motions you can see.

In our work we use flashes of X-rays coming from the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser as well as “flashes” of electrons produced in an apparatus for ultrafast electron diffraction, or UED. These pulses are very bright and last only femtoseconds. They open a new window into the atomic world.

Aaron Lindenberg

What exactly is “ultrafast electron diffraction?”

In UED, we cram very energetic electrons into very short pulses and send them through our samples. The electrons get deflected into a detector, where they produce a characteristic pattern that encodes the precise positions of all the atoms in the sample. Repeating the experiment at different points in time after the sample was stimulated and observing how the pattern changes tells us exactly how the atoms are moving. Experiments at LCLS basically work the same way, using X-rays instead of electrons.

Aaron Lindenberg

So why do you combine X-ray and electron techniques?

Because the techniques are very complementary. Each has certain technical advantages when looking at particular kinds of samples, and they also teach us different things about a material.

Let me give you an example. My group is very interested in the possibility of manipulating two-dimensional materials with light. With UED, we were able to see that femtosecond light pulses lead to large, ultrafast rippling of single atomic layers of these materials. At LCLS, looking at samples consisting of many 2-D layers, we discovered that light can be used to manipulate the bonding between the layers and, surprisingly, push the layers together at the atomic scale. Both studies uncovered totally different responses and suggest different ways of modifying the optical and electronic properties of 2-D materials.

Aaron Lindenberg

What do you hope to achieve in the future?

For me, the near future is about really grasping what determines how materials and devices function. The fact that we’re getting better at understanding more and more complex systems and are able to visualize the very first microscopic, ultrafast steps that determine the functionality of materials can really have a huge impact on how we engineer new materials. It’ll allow us to go further than just look at what happens on the atomic scale; it could help us find useful ways of using light or other stimuli to direct materials into states in which they have useful and novel properties.

I’m also excited about the upgrade of LCLS and potential developments in UED, which in a few years will make it possible to study ultrafast atomic motions in materials in their natural environments. At the moment, we need to blast materials with extremely powerful laser, electron and X-ray beams to generate large enough signals that we can analyze. However, we don’t always fully understand the effects of these intense beams. When we study solar cell materials, for example, we would really like to be able to shine only as much light on our sample as the sun would. This would give us results that are potentially closer to real-world applications.

Aaron Lindenberg