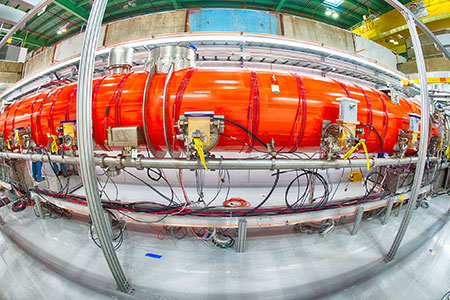

The first cryomodule has arrived at SLAC. Linked together and chilled to nearly absolute zero, 37 of these segments will accelerate electrons to almost the speed of light and power an upgrade to the nation’s only X-ray free-electron laser facility.

An area known for high-tech gadgets and innovation will soon be home to an advanced superconducting X-ray laser that stretches 3 miles in length from the beginning of the accelerator to the end of the experimental halls, built by a collaboration of national laboratories. On January 19, the first section of the machine’s new accelerator arrived by truck at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park after a cross-country journey that began in Batavia, Illinois, at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

These 40-foot-long sections, called cryomodules, are building blocks for a major upgrade called LCLS-II that will amplify the performance of the lab’s X-ray free-electron laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS).

“It required years of effort from large teams of engineers and scientists in the United States and around the world to make the arrival of the first cryomodule at SLAC a reality,” says John Galayda, SLAC’s project director for LCLS-II. “And it marks an important step forward as we construct this innovative machine.”

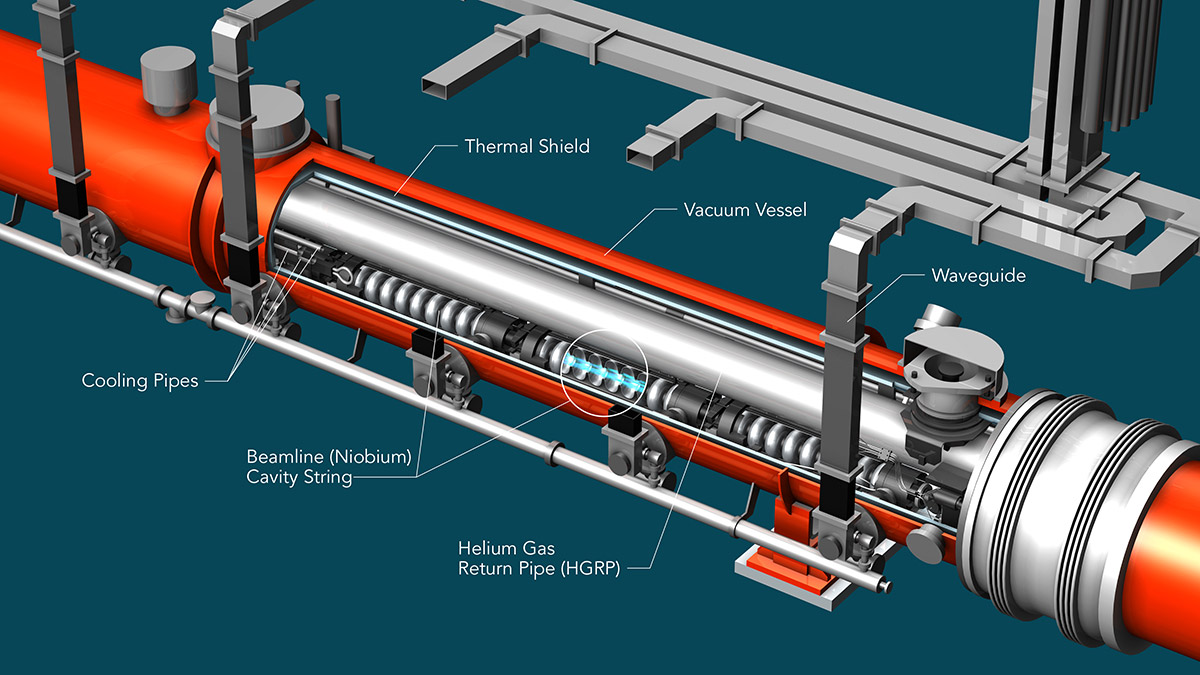

Inside the cryomodules, strings of super-cold niobium cavities will be filled with electric fields that accelerate electrons to nearly the speed of light. This superconducting technology will allow LCLS-II to fire X-rays that are, on average, 10,000 times brighter than LCLS in pulses that arrive up to a million times per second.

With these new features, scientists have ambitious research goals: examine the details of complex materials with unparalleled resolution, reveal rare and transient chemical events, study how biological molecules perform life’s functions, and peer into the strange world of quantum mechanics by directly measuring the internal motions of individual atoms and molecules.

“…this will allow scientists to do things they can’t do anywhere else in the world.”

- Marc Ross

Video Credit: Robert Kish, Farrin Abbott & Greg Stewart / SLAC

SLAC Accelerator Physicist Marc Ross explains how the lab's new superconducting accelerator will be built.

“…this will allow scientists to do things they can’t do anywhere else in the world.”

- Marc Ross

Video Credit: Robert Kish, Farrin Abbott & Greg Stewart / SLAC

SLAC Accelerator Physicist Marc Ross explains how the lab's new superconducting accelerator will be built.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is building half of the cryomodules for the LCLS-II laser upgrade, and Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Newport News, Virginia will build the other half. Fermilab, Jefferson Lab and SLAC are Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science laboratories.

After constructing the cryomodules, Fermilab and Jefferson Lab are testing each one extensively before the vessels are packed and shipped by truck. Their new home in California will be the tunnel formerly occupied by a section of SLAC’s 2-mile-long accelerator, located 30 feet below ground. In tribute to their Bay Area destination, the cryomodules are painted “international orange” to match the Golden Gate Bridge.

See more photos of the cryomodule's arrival at SLAC on Flickr.

A Super-Cool Refrigeration System

SLAC engineers and their partners are building a cryoplant refrigerator—a powerful chilling plant that will contain the compressors, pumps and helium needed to keep the accelerator at 2 degrees Celsius above absolute zero (or minus 456 degrees Fahrenheit), about the same temperature as outer space.

Credit: Greg Stewart / SLAC

At these low temperatures, the accelerator becomes what’s known as superconducting, able to boost electrons to high energies with minimal energy loss as they travel through the cavities. By the time the electrons pass through all 37 cryomodules, they'll be traveling at nearly the speed of light.

Once the electrons reach such high speeds, they pass through a series of strong magnets, called undulators, which bounce the electron beam back and forth to generate an X-ray laser beam that’s much brighter than the current LCLS, moving from 120 pulses per second to 1 million pulses per second—far beyond any other facility in the world.

Credit: Dawn Harmer / SLAC

A total of 12 warm helium compressors, designed and built by Jefferson Lab, will be installed into the cryoplant building. The cryoplant will feed liquid helium into the superconducting linear accelerator.

When the oscillating voltage in each cavity is timed to the rhythm of electron bunches passing through the cavities, the electrons get a boost of energy and accelerate.

“If a tuning fork—another type of resonator—had the same performance quality as one of these superconducting cavities, it would ring for well over a year,” says Marc Ross, a SLAC accelerator physicist who is leading the development of the cryomodules. “Superconductivity allows the cavities to accelerate the electrons in a steady, continuous wave without interruption, and with extremely high efficiency.”

Credit: Greg Stewart / SLAC

Cutaway image of a cryomodule. Each large metal cylinder contains layers of insulation and cooling equipment, in addition to the cavities that will accelerate electrons. The cryomodules are fed liquid helium from an aboveground cooling plant. Microwaves reach the cryomodules through waveguides connected to a system of solid-state amplifiers.

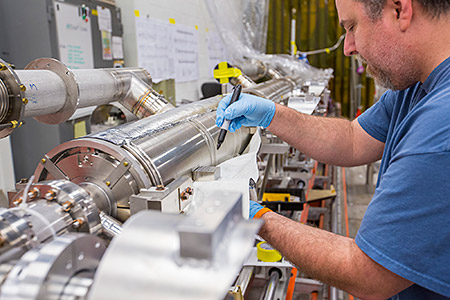

The element niobium is a common material for superconductors, and the cavities are made with an extremely pure version to minimize any electrical loss. Eight niobium cavities are bolted together in a string inside each cryomodule. They’re assembled like “a ship in a bottle,” Ross says. The cavities are surrounded by three nested layers of cooling equipment, with each successive layer lowering the temperature until it reaches nearly absolute zero.

For LCLS-II, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory also created a new advanced “electron gun” to inject electrons into the accelerator and, with significant design contributions by Argonne National Laboratory, specialized undulators to generate the X-rays.

Credit: Roy Kaltschmidt / Berkeley Lab

A prototype LCLS-II undulator, which is designed to wiggle electrons, causing them to emit brilliant X-ray light, undergoes magnetic measurements at Berkeley Lab.

SLAC’s Historic Linac: Then and Now

SLAC has a history of taking on large projects since the lab’s birth more than five decades ago. “Project M” (for “Monster”), the construction of a particle accelerator that stretches 2 miles in length, allowed scientists to study the building blocks of the universe. This linear accelerator was the longest ever constructed.

In 2009, the lab repurposed one-third of the original 1960s-era copper accelerator to feed an electron beam into LCLS, the first laser of its kind that produces rapid pulses of “hard” or high-energy X-rays for innovative imaging experiments. Another one-third of that original copper linac has now been cleared to make room for the arrival of the new superconducting cryomodules.

This project is supported by DOE’s Office of Science. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Press Office Contact: Andrew Gordon, agordon@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-2282

Text & Production: Amanda Solliday

Graphics: Greg Stewart, Terry Anderson

Video: Robert Kish, Farrin Abbott, Greg Stewart, Andy Freeberg

Photos: Andy Freeberg, Dawn Harmer, Matt Beardsley, Fermilab, Jefferson Lab, Berkeley Lab

Editing: Angela Anderson, Glennda Chui

Web Design: Yvonne Tang

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.