Cover photo: Research associate Megan Mayer and graduate student Patrick Mitchell load a sample into one of SLAC's new cryogenic electron microscopes. (Andy Freeberg / SLAC)

The new facility provides revolutionary tools for exploring tiny biological machines, from viral particles to the interior of the cell.

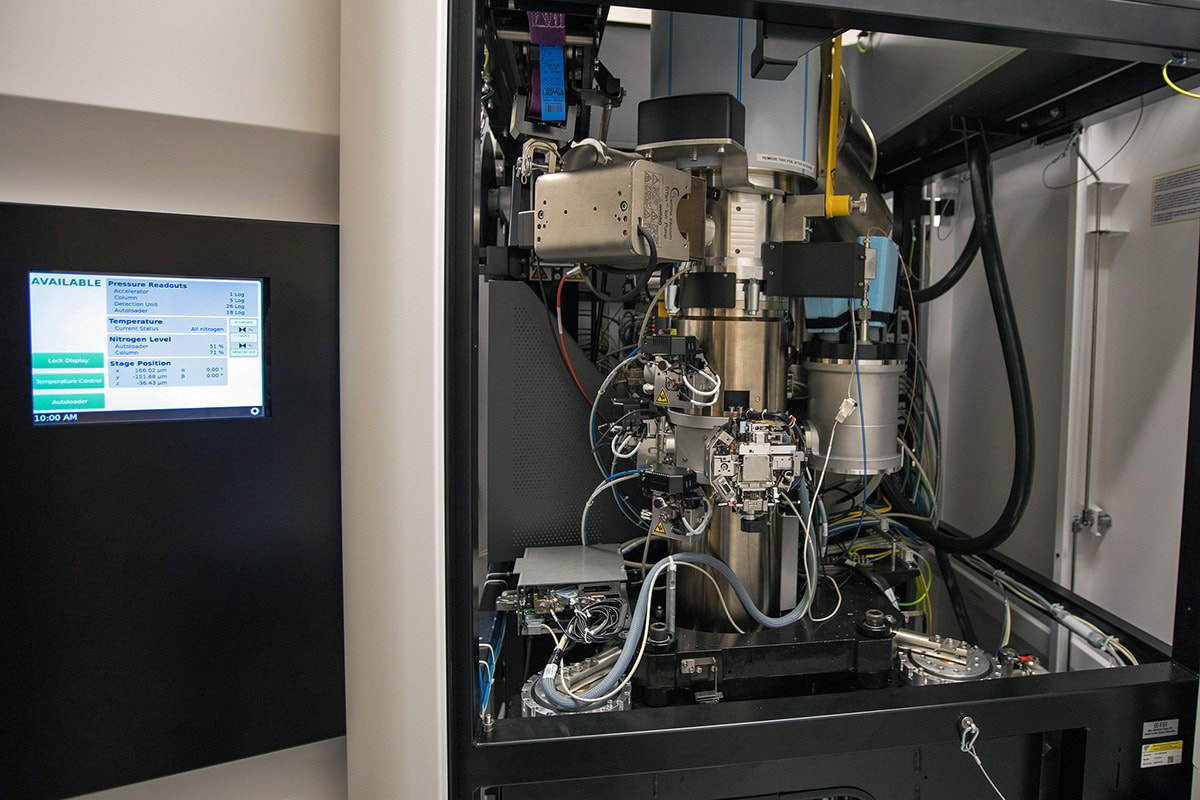

A new facility for cryogenic electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, has opened at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Built and operated in partnership with Stanford University, it’s equipped with four state-of-the-art instruments for cryo-EM, a groundbreaking technology whose rapid development over the past few years has given scientists unprecedented views of the inner workings of the cell.

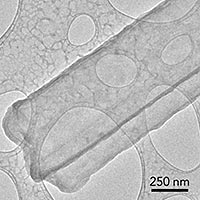

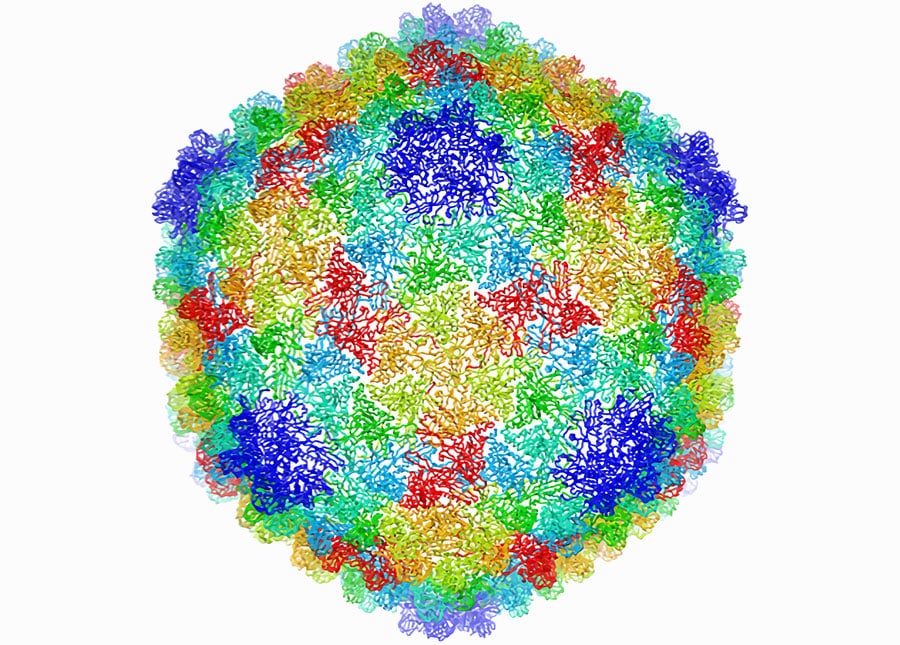

Some viruses infect bacteria; this virus particle has a shell that consists of 60 identical units, each containing seven copies of a single protein (each of the seven copies in a given unit is a different color here). This model of the shell structure, derived from cryo-EM images, reveals how the virus seals up and protects its DNA. (DOI:10.1073/pnas.1621152114)

The facility is the first to open as part of the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Initiative, and it is one of the most advanced in the world in terms of the number of high-end instruments and level of expertise it makes available. One of the goals of the cryo-EM initiative is to push the technology even further to get ever more detailed 3-D images of DNA, RNA, proteins, viruses, cells and the tiny biological machines within the cell, revealing how they change shape and interact in complex ways while carrying out life’s functions.

The facility allows researchers to prepare samples, collect data at high speed and assess the quality of that data on the fly so they can make the best use of their experimental time. They can carry out experiments in person or remotely.

“This facility is the result of several years of work and planning by faculty and other leaders at SLAC and Stanford, and it’s a great example of the opportunities our partnership brings us,” said Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne. “Cryo-EM has become an essential tool for research, especially in structural biology, and we’re excited that this state-of-the-art facility is finally here.”

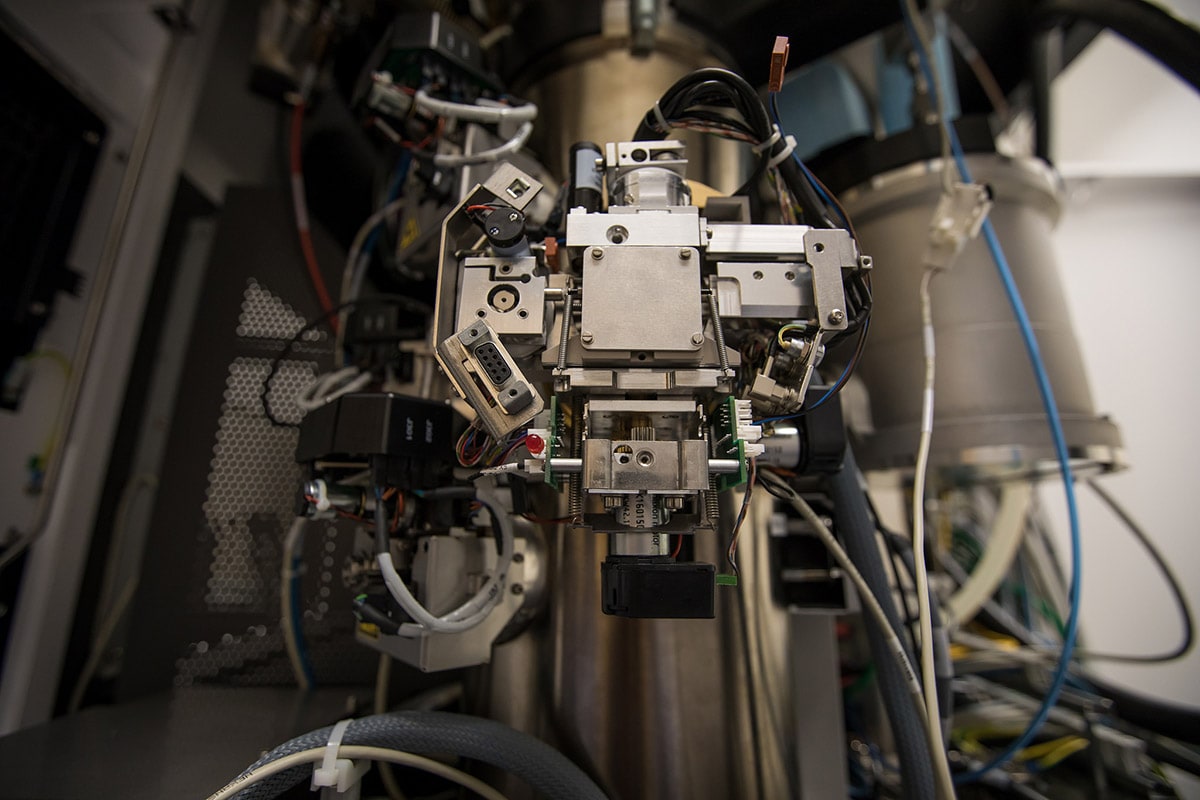

The new Stanford-SLAC cryo-EM facility is equipped with Thermo Scientific™ Krios™ (upper left) and Talos™ Arctica (upper right) electron microscopes and a suite of labs for sample preparation (bottom row). (Dawn Harmer & Andy Freeberg / SLAC)

See more photos of the Stanford-SLAC cryo-EM facility on Flickr.

An Unprecedented View of Life's Machinery

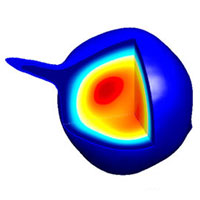

Like many other viruses, HIV carries its genetic information in RNA. This illustration shows a small piece of HIV’s RNA genome that is essential for packaging the entire genome into new virus particles. The illustration combines a 3-D cryo-EM map of the RNA structure (gray mesh) with an atomic model (red and blue) that incorporates additional data from NMR imaging and computer simulations of its motion. (DOI:10.1016/j.str.2018.01.001)

Cryo-EM is a version of electron microscopy, which was invented in the 1930s. These microscopes use beams of electrons rather than light to form images of samples. Because the wavelength of an electron is much shorter than the wavelength of light, electron beams reveal much smaller things.

In the mid-1970s, scientists came up with the idea of freezing samples to preserve the natural structure of biological specimens and reduce damage from the electron beam, and cryo-EM was born. The technology slowly evolved, and then a few years ago took a giant leap, thanks to dramatic advances in detectors and software. In 2017 three scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their roles in developing cryo-EM.

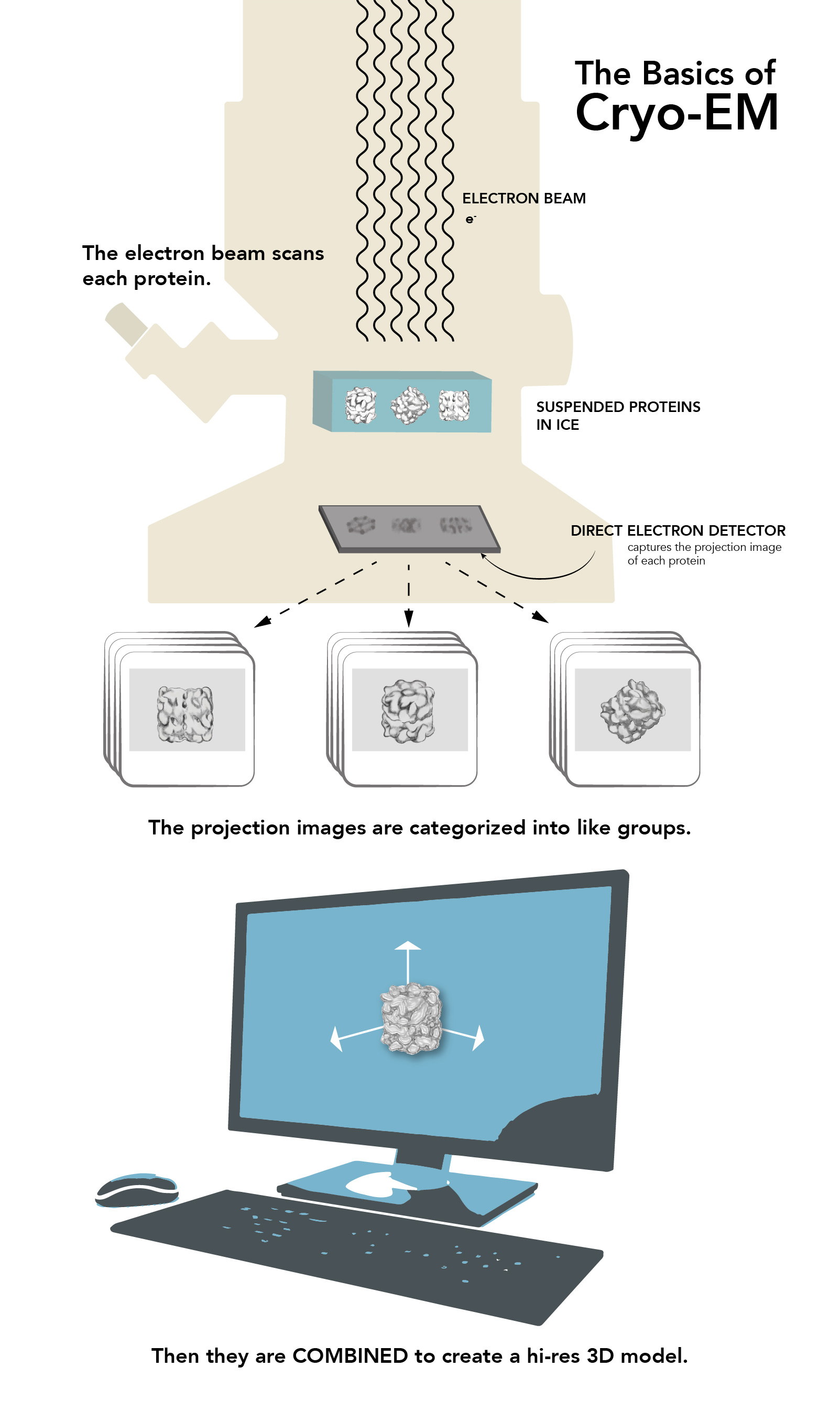

This infographic explains the basics of cryo-EM. (Farrin Abbott / SLAC)

Cryo-EM lets you capture snapshots of proteins and other biological nanomachines as they assemble, carry out their work and disassemble again.”

— Wah Chiu, SLAC and Stanford Professor

Today, cryo-EM generates 3-D images at nearly atomic resolution of viruses, molecules and complex biological machines inside the cell, such as the ribosomes where proteins are synthesized. By flash-freezing these tiny things in their natural environments, scientists can see how they are built and what they do in much more detail than before, stringing thousands of images together to create stop-action movies and even taking virtual “slices” through cells, much like miniature CT scans. Meanwhile, cryo-EM instruments have become easier to use and much more accessible.

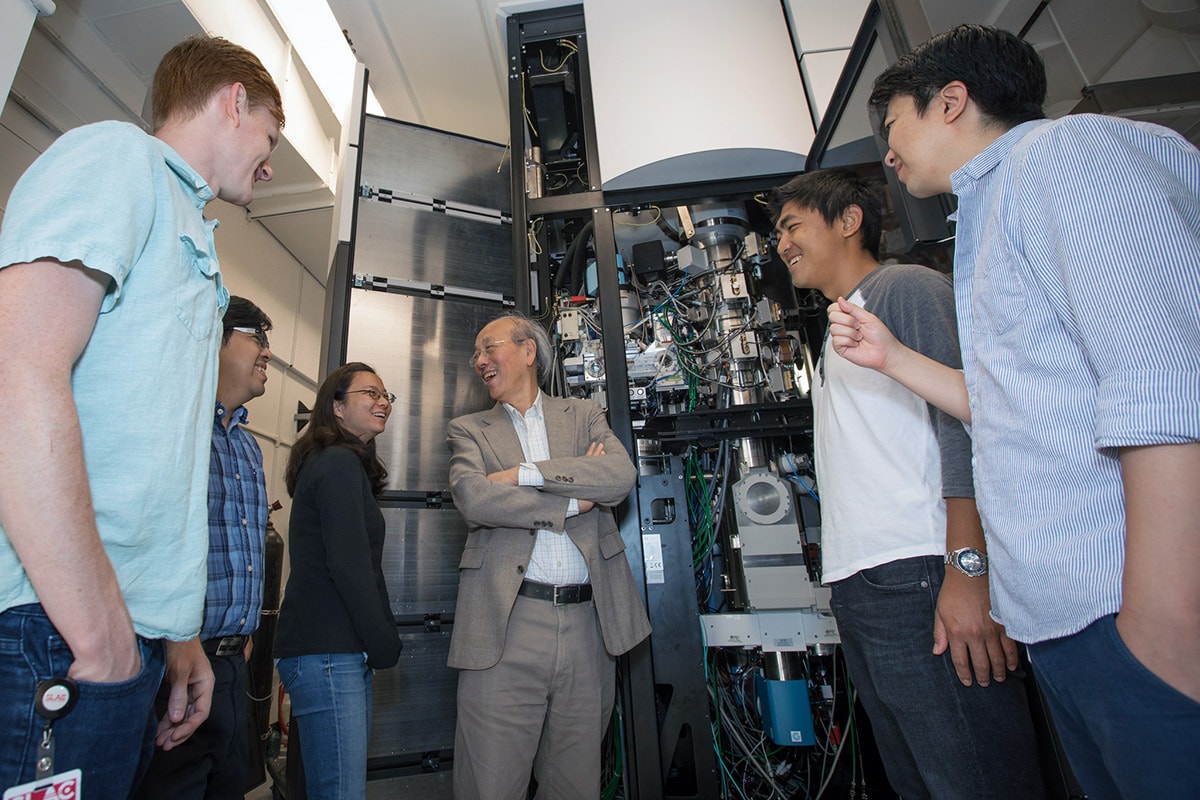

“In biology, everything is dynamic, always moving around and changing. Cryo-EM lets you capture snapshots of proteins and other biological nanomachines as they assemble, carry out their work and disassemble again,” said SLAC and Stanford Professor Wah Chiu, one of two faculty members hired last year who bring decades of experience in cryo-EM research and technology development.

Professor Wah Chiu and members of the new Stanford-SLAC cryo-EM team stand in front of a cryo-EM instrument as work nears completion on their new facility at SLAC. (Dawn Harmer / SLAC)

“A protein may multitask, changing its shape for each of its functions,” Chiu said. “From how it looks, you can determine how to modify its shape and consequently its functions—for instance, if you want to block its activity with a vaccine or develop a medication that fits into a particular pocket and triggers a response that fights disease.” He added that his own ambition is to be able to look at these biological machines at work while they’re still inside the cell, without having to remove or purify them.

Stanford Professor Georgios Skiniotis arrived last year from the University of Michigan. He specializes in studies of complex receptors on the cell’s outer membrane that are important targets for drug development, but whose structure and function are still poorly understood. Cryo-EM makes them much easier to study in detail.

“Many refer to it as the cryo-EM revolution, but I view it more as accelerated evolution because most of these concepts and tools have been steadily evolving for many years,” Skiniotis said. “Without any sense of exaggeration, the technology offers unprecedented imaging capabilities. Cryo-EM can be used for so many purposes.”

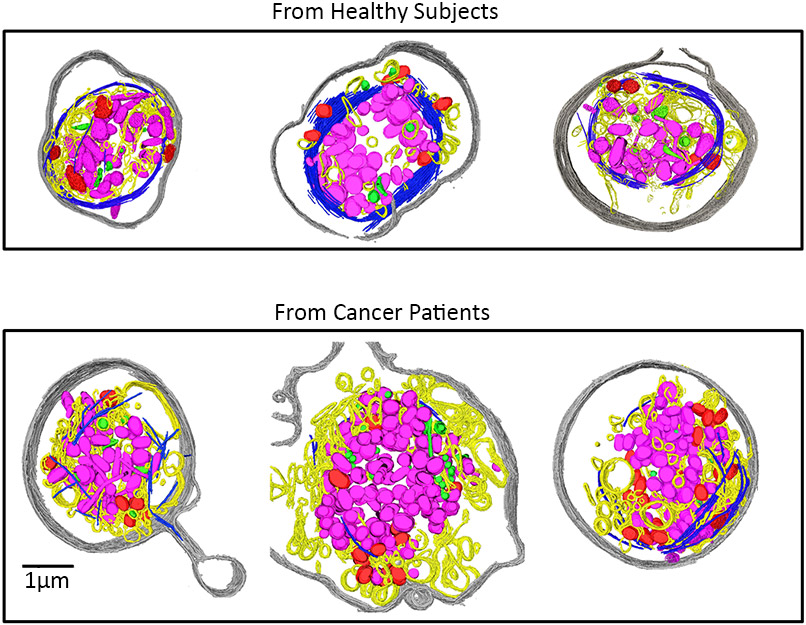

These cryo-EM images show how ovarian cancer changes platelets in a patient’s blood. The cells in the top row are from healthy people, and have a continuous circular ring of microtubules (dark blue). In platelets from ovarian cancer patients, bottom, those rings are shorter, broken and disrupted. These changes might someday offer a way to diagnose the disease. (DOI:10.1073/pnas.1518628112)

In battery research, for instance, scientists working with an older cryo-EM instrument at the Stanford School of Medicine recently captured the first atomic-level images of finger-like growths called dendrites that can pierce the barrier between battery compartments and trigger short circuits or fires.

“With cryo-EM you can look at a material that’s fragile, chemically unstable, and you can preserve its pristine state—what it looks like in a real battery—and look at it under high resolution,” said Yi Cui, a professor at SLAC and Stanford who led the study. “This is tremendously exciting, a huge opportunity, and it could explode the whole field of materials design.”

Another plus is the lab’s long tradition of assisting visiting scientists with complicated projects, said Britt Hedman, a SLAC professor and science director for the lab’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. “SLAC has done this for 40 years or more,” she said. “We provide instrumentation, expertise and training, and we work with them to make sure their experiments are successful. Now we’ll be making this legacy of know-how available to the scientists who come to do experiments at the new cryo-EM facility.”

SLAC research associate Megan Mayer peers into a device that uses plasma to clean the gridded discs that hold biological crystals for study. (Andy Freeberg / SLAC)

Both Chiu and Skiniotis have been collaborating with Stanford scientists on research projects over the years, and that’s even easier now that they—and the cryo-EM facility—are close by, Chiu said.

“I think the environment of physicists, engineers, computational scientists and chemists around the SLAC and Stanford campuses can inspire us to think differently,” he said. “There’s no doubt in my mind that this will lead to new approaches in specimen preparation, data collection, image processing – in the whole pipeline.”

Chiu brings with him two National Institutes of Health research programs he started while at Baylor College of Medicine. One is a regional consortium for cryo-EM data collection; it makes instruments available to cryo-EM scientists across the United States who would not otherwise have access to the technology. The other, a national center for 3-D electron microscopy of macromolecules, is focused on cryo-EM technology development that is driven by the biomedical projects of collaborators around the globe, as well as on training and serving the global community of cryo-EM researchers.

Press Office Contact: Andrew Gordon, agordon@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-2282

Text: Glennda Chui

Photos: Andy Freeberg, Dawn Harmer

Infographic: Farrin Abbott

Editing: Angela Anderson

Web Design: Yvonne Tang

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

NCMI is a National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Biomedical Technology Research Resource.